Response to NYT: Western Observers Stumble in Assessment of Offensive

Published 1 years ago

An old aphorism states that no plan survives contact with the enemy, a situation evident as Ukraine attempts to drive Russian invaders from their homeland. Ukraine’s U.S. and NATO supporters anticipated that the donation of advanced western tanks, armored vehicles, artillery systems, and other capabilities, as well as training, would grant the Ukrainian army a decisive advantage over their Russian opponents, and many government officials and observers have expressed frustration in the slow progress of this summer’s offensive. A recent article published by the New York Times claims that western-trained Ukrainian troops have “stumbled” on the battlefield, noting that Ukraine seems to have abandoned its western training in combined arms tactics for an attritional approach. The article makes two assertions, the first being that Ukrainian struggles can be seen as an indictment of the western way of war, and the second that the Ukrainians are not effectively employing the tools they have been given. I do not entirely agree with either statement, and with all due respect to the authors of this article, both of whom have done some excellent reporting in the past, this piece represents a lack of understanding of combined arms, of the capabilities that Ukraine has been given (and what they have yet to receive), and of the tactical problem faced by the Ukrainian army. While no individual, unit, or belligerent army in this conflict is perfect, the Ukrainian army has managed to created combined arms effects within the constraints posed by their tactical situation and the resources available; they are attempting to integrate various equipment sets and to adopt a doctrinal approach without all of the required capabilities; and they are attempting to find the best solution for a tactical problem which would pose a challenge to any military, including the U.S. armed forces.

What is Combined Arms?

The United States military defines combined arms as “the full integration of arms in such a way that to counteract one, the enemy must become more vulnerable to another.” Tanks, infantry, armored vehicles, artillery, and airpower are employed in a coordinated fashion with a goal not merely of destroying the enemy’s physical assets but by disrupting his ability to function. The U.S. military and its allies accomplish this synchronizing the seven warfighting functions - command and control, fires, force protection, information, intelligence, logistics, and maneuver – to allow all force components to focus their efforts on a common objective. Simultaneously, allied forces will employ fires, maneuver, electronic warfare/electronic attack (EW/EA), and information operations to destroy enemy cohesion and eliminate his ability to fight as a cohesive force. These are the core components of maneuver warfare, which seeks to defeat an opponent by a combination of preemption, deception, dislocation, and disruption, leading to moral collapse, as opposed to attrition, which seeks the physical destruction of an opponent by applying superior force and mass.

The German Blitzkrieg of 1940 and 1941, and the coalition dismemberment of the Iraqi army in 1991 and 2003 are examples of combined arms and maneuver warfare, while the trenches of the Western Front in World War I are emblematic of campaigns of attrition. Modern western doctrine emphasizes campaigns of maneuver and the avoidance of attritional battles, and U.S. and NATO equipment sets and operational approaches reflect a commitment to that philosophy. The effect has been a brand of amnesia amongst western observers and the development of unreal expectations. Though World War II ushered in the age of the tank, maneuver warfare was only made possible by the precise, coordinated application of airpower and artillery fires, and many campaigns, particularly in North Africa, Italy, and France, were deadlocked in contests of attrition until a breach, often gained at great expense, made possible an armored thrust into the enemy rear. Yet in the west its sophisticated land systems, such as the Abrahms, the Leopard 2, and the Challenger II are seen as the keys to victory, rather than components of a complex system, and for western observers, particularly in the U.S. and Britain, they are synonymous with rapid maneuver and complete victory. These perceptions have led to unrealistic expectations for Ukraine and its current offensive.

Systems and Capabilities

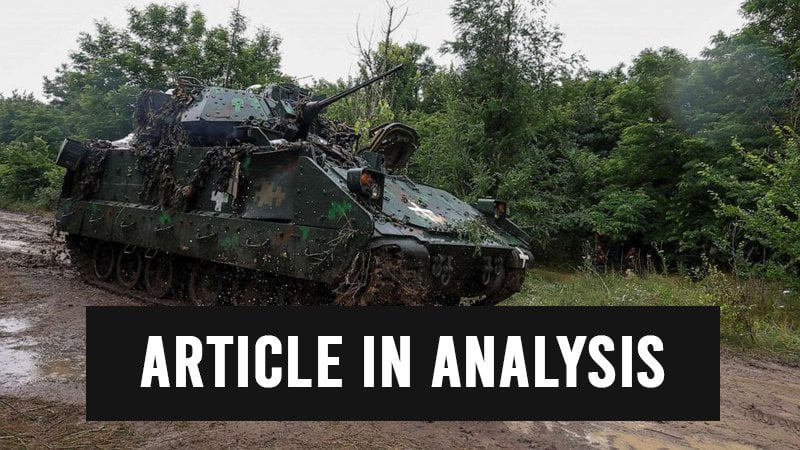

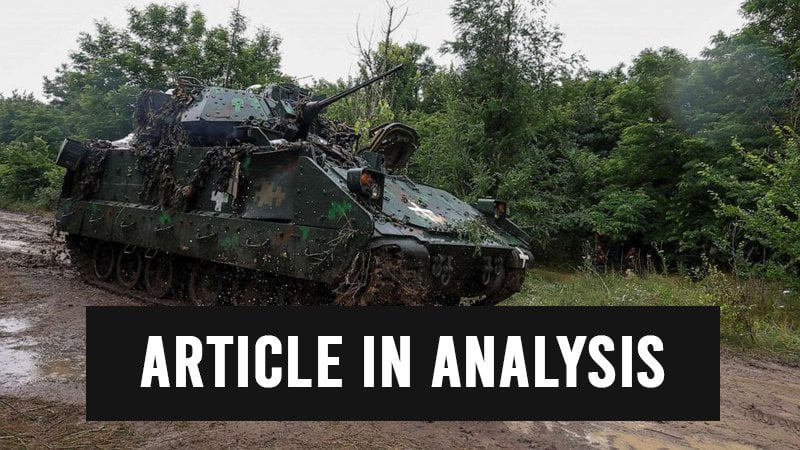

In the past eighteen months western systems have drastically enhanced Ukrainian combat capabilities, and the Ukrainian Army has made good use of the kit. The Javelins and N-LAWs delivered early last year helped stop the Russian armored advance; artillery systems such as HIMARs have allowed the Ukrainians to develop an interdiction campaign that has disrupted the Russian system and significantly degraded its offensive capabilities; western anti-air systems have protected Ukrainian cities and logistics hubs; and western armor has provided lethal fires as well as enhanced protection. That last point has gone largely unrecognized in the press and by observers. The vulnerability of Russian armor has been amply demonstrated over throughout this conflict, and while picture of damaged Leopards and Bradley infantry fighting vehicles (IFVs) are disheartening, their survivability is questioned, and the crews (and their families) are doubles thankful to be spared immolation and to live to fight another day, while many of the vehicles remain salvageable. The capabilities that the Ukrainians lack are deep fires, sufficient artillery tubes and ammunition stockpiles for massed artillery fires, the ability to conduct a vertical or an amphibious envelopment, and airpower which can support maneuver.

The Tactical Problem

Ukraine is forced to make do with the capabilities currently in its possession as it ponders a complicated tactical problem. Maneuvering around the Russian strongpoints is not a solution, for the Russians have created a continuous defensive line reminiscent of World War I, extending from Kherson in the south to the Russian border in the north and prepared with trenches, barbed wire, tank obstacles and mines millions of mines in concentrations that have not been seen since World War II. How would the U.S. or NATO face such a challenge. First, they would likely not have waited for the establishment of a continuous defensive line and would have struck into the Russian rear before it was completed, but Ukraine did not possess much of its kit a year ago and many of its new units were recently formed and untrained. Perhaps they would conduct an amphibious landing, or at least an amphibious feint or demonstration, and early on they would establish complete air and naval dominance, but Ukraine possesses none of these capabilities.

The Ukrainian Army cannot circumvent this barrier, as the Germans did with the French Maginot Line in 1940. An envelopment to the north would involve either an invasion of Belarus, which would bring that country into the war, or a lunge through Belgorod Oblast, which the Ukrainians cannot logistically sustain, and which might prompt a drastic response from the Kremlin. In the south, the Ukrainians face relatively thin Russian defenses on the left bank of the Dnipro River, opposite Kherson, but they lack sufficient amphibious capability to conduct an opposed crossing of the river and do not possess the gun tubes or ammunition stockpiles to provide sufficient fires to support such an attack. So there is nothing for it but to punch a hole through the line, and then drive maneuver elements through that hole, wreak havoc in the Russian rear, and cause the front to collapse. Such operations are costly in terms of ammunition, equipment, and people. A massed assault against one sector would result in the commitment of Russian reserves to that location, and so the line must be engaged at multiple points to fix Russian units in place. A breach requires massed fires to suppress enemy front line defenses, as well as deep fires to interdict Russian reserves, disrupt their logistics, and suppress their indirect fires and air defense assets. Finally, an actual breach of defensive fortifications requires substantial combat engineering assets and the clearing of obstacles and mines while under fire. The Ukrainian Army must accomplish all of this with a limited number of tanks, armored vehicles, artillery tubes, ammunition, and no air power.

A Shift in Tactics

Ukraine’s recent shift in tactics represents adaptation in recognition of their own operational limitations in tackling this tactical problem, and not necessarily a misuse of western kit or an abandonment of the western way of war. Western kit and operational methods were designed to work as a system that includes and is dependent on air and naval dominance, two capabilities Ukraine lacks. Within existing constraints, the Ukrainian Army has managed to develop remarkable tactical skill at the small unit level and to achieve limited combined arms effects at the tactical and operation levels. The footage that is available reveals an army that displays remarkable skill at the small unit level. In the absence of air power, artillery has served as the source of shaping and supporting fires, but shortages in artillery tubes and ammunition have forced the Ukrainian Army to be selective in their targeting. They have mounted an inspired interdiction campaign and their counterbattery fires have whittled away at Russia’s numerical superiority in gun systems. However, even with the acquisition of large quantities of 155mm DPICM to bolster their dwindling ammunition stocks, they likely do not possess the guns or the rounds to deliver that massed fires required to support a breaching operation that can punch a gap in the Russian lines to enough to drive several brigades into the Russian rear and sever the Russian land bridge with Crimea.

The decision to shift strategies and to attempt to achieve an asymmetrical attrition gradient is not so much a rejection of the combined arms philosophy as it is an acceptance of what can be achieved with the tools at hand. One of the objectives of maneuver warfare and the combined arms approach is to disrupt the enemy system as a whole, and the Ukrainians have correctly identified Russia’s deficiencies in command and control, logistics, and cohesion as vulnerabilities that can be exploited. Additionally, the absence of Russian operational reserves which can counter a breach in the main defensive belt has been known for some time. Using drones, loitering munitions, highly accurate artillery systems, HIMARS, and EW/EA assets they target logistics, enemy IDF and air defense systems, communications networks while maintaining consistent pressure on front line defenses, degrading the capabilities of the defenders and exhausting local reserves. Continued operations near Bakhmut offer an opportunity to attack in an area in which the defenses are less prepared and has served to draw in and fix in place more capable Russian units which might otherwise be committed elsewhere on the battlefield.

While there is open-source intelligence in abundance regarding Ukrainian operations we know little about their operational planning. The western way of war is more than just air dominance and high-tech systems, it is a process and a philosophy. Successful operations are the result of staff officers at the battalion-level and above engaging in processes that result in a clear, flexible plan that synchronizes all warfighting functions and that focuses all resources in achieving operational objectives. Learning these processes would have been a component of U.S. and NATO training, and the degree to which this structure has been embraced by the Ukrainians is unknown. Even if Ukrainian staffs have wholeheartedly adopted the allied joint doctrine for planning operations, building that sort of operational culture takes time, and no amount of planning can change deficiencies in capabilities like those already discussed.

Of course, the Ukrainians may have taken the kit with a nod and a handshake, tossed the rule book out the window, and then gone about things as they see fit, but I do not think that is the case, at least not entirely. What we do know is that they face a tactical problem which allied planners, particularly Americans, have not faced since the World War II: breaching the prepared defenses of a near-peer opponent without the benefit of air superiority. I do not know how U.S. or NATO forces would handle this situation, given these constraints. Do we possess sufficient artillery to compensate for the absence of air-delivered munitions? Do we possess sufficient combat engineer assets to breach a prepared defense so heavily saturated with mines? Could we adapt to the threat posed by drones and loitering munitions? What I do know is that Leopard tanks and Bradley IFVs are not magic talismans, they are not immune to artillery and anti-tank guided missiles, and they can not miraculously slip through Russian fortifications. I also know that Ukrainian commanders are not accepting casualties because they wish to, but because they must.

This is not to offer the Ukrainian Army a complete pass, to absolve them of bad calls or errors in judgement. On any battlefield the heroes and buffoons often fight side by side, and on some days even the best of commanders can fail while the worst can sometimes find success. But they have accomplished much when many thought they would fail, and this must be appreciated. Viewing Ukrainian actions through a uniquely western lens and setting unrealistic expectations for outcomes on the battlefield is unproductive. The conflict in Ukraine must be judged on it own merits, within the context of the present operational conditions, and with an appreciation for their operational constraints. Those in the West may share frustration at the financial cost of supporting this conflict, but the price in blood will ultimately be paid by the Ukrainians, and thus it is up to them to adapt to conditions as they see fit.

About the Author

Cam

Cam served as an infantry officer in the Marine Corps, deploying to the Horn of Africa and participating in combat operations in Iraq. He currently works in the maritime industry and in the defense sector as an instructor of combined arms planning and operations. An avid sailor, Cam founded and directs a nonprofit that supports veterans and first responders through sailing.